I first heard about Horrocks when she visited Ball State University (where I'm getting aforementioned degree), and she's an interesting author as well as an engaging speaker. During the visit, she talked about how some of her stories are the result of challenges or exercises she sets for herself. For example, the first story in the collection, "Zolaria," came from Horrocks deciding to write a story that went forward as well as backward in time.

That idea of stories as challenges stuck with me, and now as I'm reading This Is Not Your City, I'm trying to reverse engineer the finished stories back to the original challenge. I haven't figured out all of them in this way (and I don't think all of them had that kind of inspiration), but the story I read this afternoon seems to have a challenge behind it.

The story is "At The Zoo," which, as the title implies, is about a grandfather, mother, and son spending the day at a zoo. It's not an especially complicated story on the surface, but as I got further in to it, I noticed it was doing something unusual.

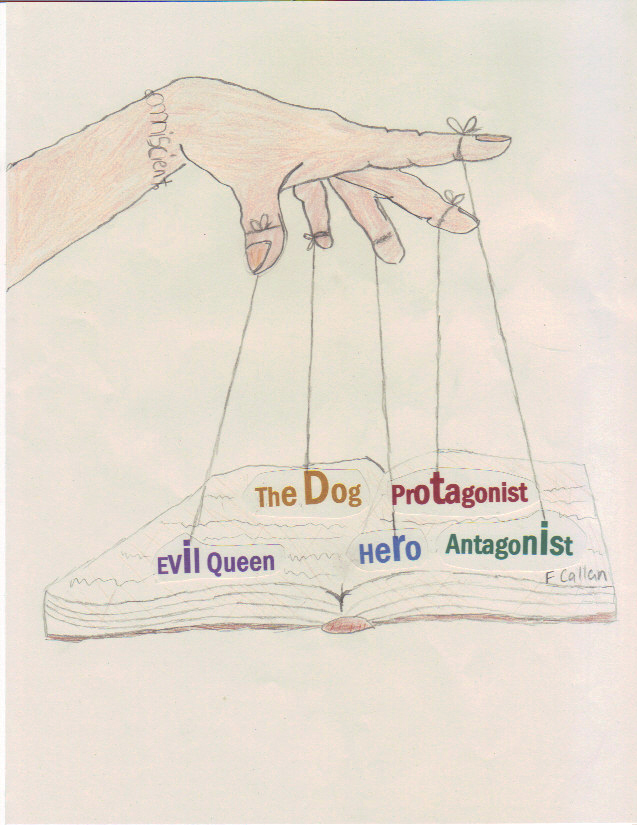

Most stories and novels (and even most other stories in Horrock's collection) these days are either written in first-person (an "I" narrator tells the story) or third-person limited omniscient (using "he, she, they," and only hearing the interior thoughts of one character in the story). People seem to think that getting in the head of more than one character is cheating or playing God or something, and it's generally discouraged.

|

| Picture from here. The bracelet around the wrist spells out "omniscient." |

In "At The Zoo," however, Horrocks moves in and out of the heads of each of the three main characters. At one point, the mother, an attorney, thinks about the mad scientist who wants to patent his time travel machine; at another, the grandfather reminisces about life with his late wife; and we also hear the boy's thoughts about how the animals must be sad to be trapped in cages. Since the thought processes and ways to expressing themselves are quite different for each character, and since there are only three of them, it's easy to keep track of whose head we're in at any given moment (one pitfall of third-person omniscient is that it can be difficult to differentiate each character's thoughts).

The challenge that I think Horrocks set for herself, then, was to write a story in third-person omniscient perspective. And she not only succeeded, but she wrote a "rule-breaking" story that is more effective and involving than it would have been had she written it from a more traditional perspective.