For a while in the early 2000s, the “what kind of Jesus do

you believe in?” dichotomy came to be represented by Mr. Rogers, on the meek

and mild side, and William Wallace (Braveheart)

on the holy warrior side.

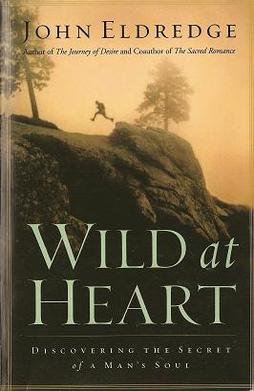

A primary source for this contrast was John Eldredge, author of the book Wild at Heart, which advocated a kind of “real man” who has “a battle to fight, a beauty to rescue and an adventure to live.” At the other end of Eldredge’s spectrum are weak, “really nice guys” like Fred Rogers.

Eldredge looked at the men in church

around him and concluded they were bored because church was not active or manly

enough. A lot of people seemed to agree with him, but Wild at Heart didn’t click with me. I wished I could be more like

Mr. Rogers. I thought Braveheart was

kind of boring.

Although Eldredge has continued to

publish books and organize Wild At Heart bootcamps, his stature in evangelical

Christianity has diminished in the past few years. The “tough guy for Jesus”

mantle has largely passed on to Mark Driscoll, pastor of Mars Hill Church,

which is based in Seattle and has network churches in several states.

Driscoll is known almost as much for cussing

during sermons and having tattoos as he is for his Reformed theology. In a Relevant

Magazine article, he described the kind of Jesus he prefers:

In revelation, Jesus is a prize fighter with a tattoo down His leg, a sword in His hand, and the commitment to make someone bleed. He is saddling up on a white horse and coming to slaughter his enemies and usher in his kingdom. Blood will flow. That is a guy I can worship. I cannot worship a guy I can beat up.

More Braveheart, less Mr. Rogers.

While I personally don’t get the visceral thrill from

watching an action movie that a lot of people seem to, I can understand why so

many of our great stories have conflict at their core. As I writer, I know

conflict is practically what makes a story a story. Without conflict, what

drives the action? Why would readers and viewers want to follow characters who

never struggle or overcome?

In some ways, stories are the opposite of real life. Imagine

a day where you got up, had breakfast with your family, dropped the kids off at

school, had a few productive meetings at work, and then went out for a nice

dinner with your friends.

Sounds like a perfect day, doesn’t it? But it wouldn’t make for

a very good movie, would it?

In life, most people want to avoid or minimize conflict, but

we seek it out in the movies we watch and stories we read.

My question is, why do we do that? Why are we drawn to watch

the kinds of experiences we would never want to live out?

Or to look at it from the other direction, can you have a

great story that doesn’t feature conflict? Could someone write an epic of

peace?

The first half of Wings

of Desire follows angels as they wander around the city, comforting and

encouraging the people of Berlin. We can see the angels—who wear dark trench

coats because the director, Wim Wenders, wanted to get as far from the

traditional portrayal of angels as he could—leaning in to listen to the hopes

and fears of the people they contact, but the characters in the movie can’t. It

makes for some awkward images (see the video below).

One of the angels’ frequent hangouts is the city library,

because a lot of lonely dreamers seem to end up there. One of those dreamers is

an elderly man named Homer, who gives a wonderful monologue about stories and peace (click on the link for the video. It won't let me embed it here):

But

no one has so far succeeded in singing an epic of peace. What is wrong with

peace that its inspiration doesn't endure, and that its story is hardly told?

So, I’m drawn to contemplative, peaceful stories, while John

Eldredge and Mark Driscoll are drawn to stories about battle-scarred heroes

vanquishing their enemies. Those biases creep into the portrayals of Jesus we

respond to, the stories we gravitate toward. Where Drsicoll envisions the tattooed

warrior Jesus of Revelation, I tend to see Jesus telling Peter to put down his sword in Gethsemane.

But Jesus is both of those images, and a thousand more besides.

A single perspective cannot fully capture him, and when we emphasize only the

one we prefer, we do a disservice to the whole, full person.